In the past, when extended families were the main family composition, maru of a hanok, the traditional Korean residential architecture, was a space to connect different generations and strengthen a sense of belonging as a family by bringing the whole family together in one space. However, in modern times, Maru has lost its shape as the residential type has changed into a multi-story building such as an apartment, and has lost its function due to changes in the type of family composition such as nuclear families and single-person households. Even so, maru remains a different appearance in Korean society. Examples include public facilities where existing hanoks are reconstructed and platforms that maintain the name and multifunctional characteristics of maru where citizens can do various activities. Also shared housing has emerged to solve the housing price problem and the loneliness of single-person households, and a new definition of a family that transcends blood ties has appeared. In modern times, maru is no longer recognized as a private space for families, but as a common space.

A good place to experiment with new maru, away from the existing context, is New Malden, London. New Malden is the largest Korean town in Europe and the third largest in the world. However, unlike other diasporic regions such as China in China town, Nigeria in Packham and Latin America in the Elephant and Castle showing the identity of dominant country, it is hard to find an identity of Korea in New Malden. Initially, Koreans gathered here because it was close to the location of the first Korean embassy in England. However, most of the Koreans living here today are not permanent residents, but resident employees, international students or people doing working holidays. Therefore, unlike other regions, which are composed of immigrants and refugees who have settled for the purpose of living, the members of New Malden are people who do not stay in London for long. This fact shows that the community will be maintained as the number of international students and people doing work holidays increases, but the members continue to change. Along with this, the number of new Koreans is rising as the number of children of people with permanent residency is increasing. Therefore, we need a space that is solid and reveals Korea’s identity to protect them.

The role of the maru in the past is expanded and adapted to the present and the form, rituals and culture are maintained through people’s direct experiences in space. For people in New Malden, the life in UK is temporary and unstable. Therefore, there are people who give up their goal due to homesickness and anxiety. They also have a closed community characteristic that is difficult to mix with mainstream British life due to the difficulty of language and culture differences. This shows that Koreans living in New Malden need a space that has an influence like their hometown to be connected to others. This space should not only show the characteristics of Korea, but also serve as a bridge to mix well with the mainstream of England. Through socializing in this space, individuals play a role in the Korean community, support each other, and form the whole.

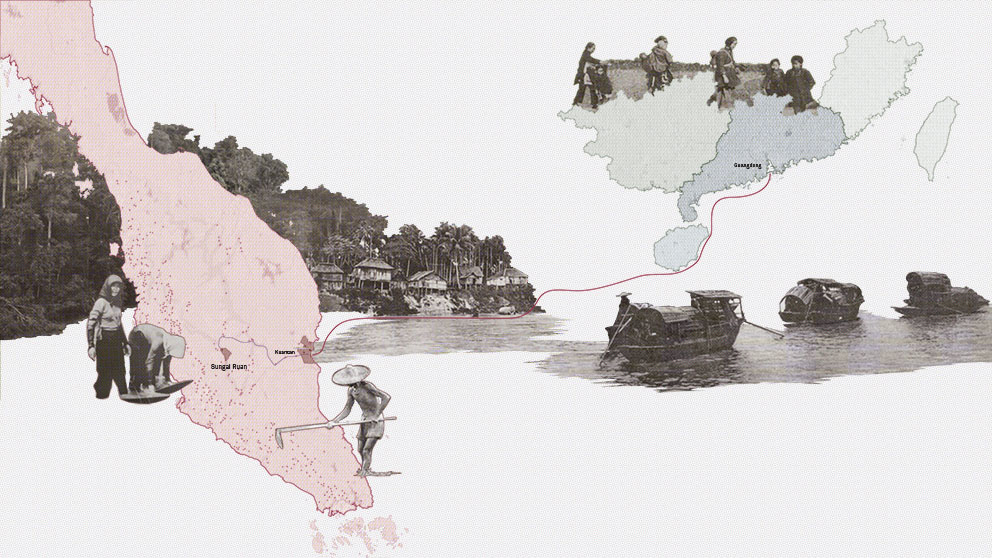

Malaysian Chinese, who formed the second-largest ethnic group in Malaysia, make up 22.8% of the Malaysian population. Most Malaysian Chinese arrived in Malaysia in two waves – in the 15th century during the Chinese Ming dynasty treasure voyages, and later on, during Malaysia’s colonial era between the 1500s and 1900s when many Chinese migrated to escape famine, war, and poverty in their home villages. They became farmers, working and cultivating the land, or miners, developing tin mines and playing a leading role in Malaysia’s tin-mining industry.

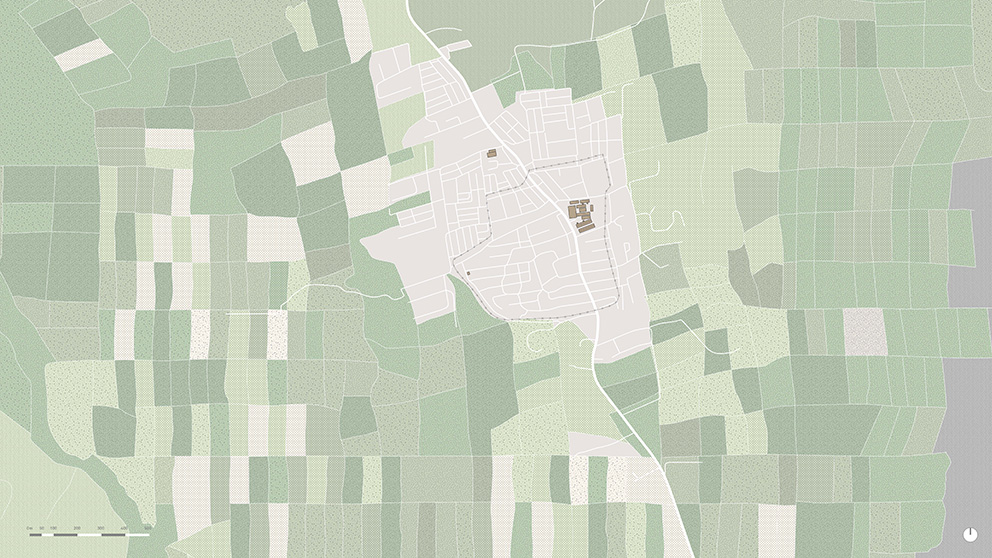

Malaysia, during the British colonial rule, was unstable. Due to political changes within China, a communist movement spread among overseas Chinese, and the communists in Malaysia fought to win independence for Malaysia from the British Empire. Between 1948 and 1960, the British colonial government implemented the Malayan Emergency, which, forced around 400,000 ethnically Chinese civilians into internment camps called New Villages. Official records document 480 New Villages created.

My family’s story as Malaysian Chinese began with my great-grandparents, who left their village in Guangdong and travelled by boat, arriving on the east coast of Malaysia in what is now the city of Kuantan. My grandparents grew up and met in Kuantan but were forcibly displaced by the British colonial government in 1955 and taken inland, where they resettled in a New Village called Sungai Ruan.